We accepted this as normal

I always knew my Dad liked a drink more than most. As a child, he was always the life and soul, and our house was fun. It was a joke that he passed out at BBQs, tore up a bathroom carpet in the middle of the night, or fell asleep on the train to the end of the line. I adored him.

My parents separated when I was a teenager, partially to do with his increased drinking. After that things got worse, and I don’t think I ever saw my Dad without a drink again. He had a serious of disastrous relationships, that all involved alcohol, violence and acrimonious endings.

I lived from my late teens in a perpetual state of anxiety that he would die. That he would drink drive and kill himself or someone else, that he would get involved in a fight, that he would fall down the stairs. The list was as endless as my imagination. The last thing I would do at night was to check my phone had the ringer on, so I did not miss a phone call to go and help.

And all this time we never spoke about the fact he was an alcoholic. We studiously avoided that word. I don’t know exactly when I realised. He had a good job, disposable income, a home and a sports car. He was well travelled and articulate. I had long used this to justify why he could not be an alcoholic. I remember speaking to an AA advisor on the phone, explaining that he couldn’t be an alcoholic, not really, as he did not put vodka on his cornflakes.

In my early twenties he went through a very bad patch; another relationship breakdown led to a suicide attempt, lots of calls in the middle of the night, and the loss of his job. At this point he really crossed the line from functioning to non-functioning alcoholic. This time I sought help from Al-Anon and even went to a meeting or two. But there was nobody there like me, no COAs, mainly spouses who were older and living a very different experience. So, on we went. Avoiding, ignoring, worrying and judging.

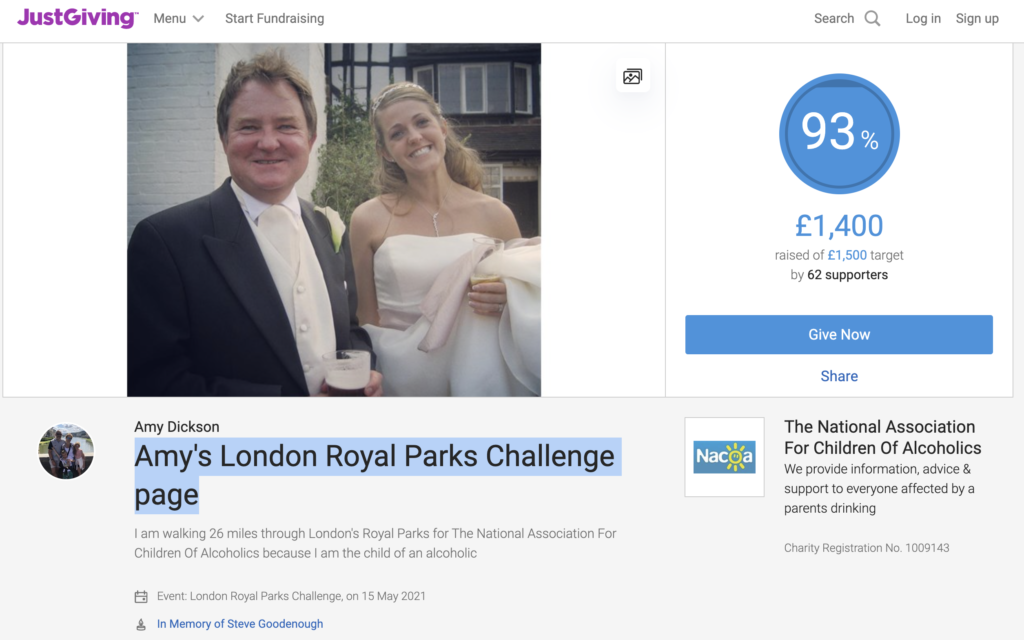

At my wedding, we had the speeches before the meal, in the knowledge that he would be too drunk to speak afterwards. We accepted this as normal. At my daughter’s Christening we had a row in the car park because he had too much to drink to drive. But drive he did, and we let him, preferring to keep our fingers crossed that he would not cause an accident rather than let him stay with us overnight.

He used to come and stay at Christmas and sleep in my young son’s bedroom. It was so stressful. His car would pull into the drive, and I would feel a mixture of relief that he had not killed anyone en route, and utter dread about the next few days. I would check his bag and find bottles of “water” in there, where he had decanted vodka to get him through the night.

I would hear the plastic bottle lids hit the wood floor in the early hours, and rarely slept when he was with us. He would never get up to see his Grandchildren’s presents being opened, and always start an argument on Christmas night. My son would complain that his room smelt bad after Dad had left, and we had to air it for hours until the stale alcohol smell had gone. But the alternative was that he would spend the holidays alone, and that was worse.

My Dad died in September 2020. He died alone, and we did not find out for several days. The police came to the door. He had not called for help. He was 68. He had a heart attack, which I like, because I can tell people that. And I can leave out the bit about why his heart stopped if I want to. That he was an alcoholic, that his drinking caused his death. That my Dad was an alcoholic, that I am that person.

I know it wasn’t my fault, I know that I could not have helped him unless he wanted help. I know all these things, yet it is still really tough. I am in my forties with my own children and it is still really tough. There is no age limit on being a COA.

Amy

Amy is running a London Royal Parks Challenge to raise funds and awareness for children affected by their parent’s drinking.

Support her on JustGiving here.