The Child of an Alcoholic: It’s never too late to break the cycle

My name is Tony. I am a child of an alcoholic. For many years, in the meeting rooms of Alcoholics Anonymous, I said, ‘my name is Tony, I am an alcoholic.’ From the perspective of being happily sober for nigh on nine years, I can now confidently say that I am not, and never have been, an alcoholic.

Yet for two decades, I wrestled with the belief that I was. I was never physically dependent on alcohol, and I did not suffer the violence of withdrawal. But I had a problem with alcohol. I was a dangerous drinker, with a tendency toward drama and a knack for being an embarrassing nuisance.

Living with shame

The shame of how I perceived myself the morning after each toe-curling episode, imagined or real, meant that I spent twenty years swinging between periods of abstinence and relapse into heavy drinking.

My drinking behaviour revealed what I now understand to be a progressive brain condition. Once alcohol passed my lips, I could not safely control my intake. I was a binge drinker, drawn to chaos, and came from a long line of it.

A family illness

My paternal grandfather died in a drinking incident at the age of thirty-three. My father, disabled by cirrhosis and alcoholic neuropathy, died in an accident at forty-nine. The warning signs could not have been starker. Had I not stopped completely, it would not have taken much imagination to see my life ending in a similar way.

But alcohol was only part of the story. The truth is that my entire adult life was shaped by a single determination: never to become my father. My childhood was scarred by his destructive drinking and brutality, directed at me, my three siblings, and mostly, my mother.

I was born in 1965, the youngest of four. My arrival coincided with a financial crisis in the family. My father, an orphan from the age of three and raised by his grandmother in the tough streets of Glasgow’s Gorbals, had just lost his well-paid job following a second arrest for drunk driving.

The blow to his pride and income triggered a spiral in his drinking that proved unstoppable and devastating for our family.

To him, I was a symbol of misfortune, a harbinger of doom. In his drink distorted mind, I was a Jonah, brought into the world to witness his downfall and steal the attentions of his wife. A man of many names: Willie to his drinking pals, Bill to my mother, Daddy, then Faither, and eventually far worse, as our love and respect for him faded with each assault.

Living with a father’s resentment

In the early years, my mother protected me. Without her, I might not have survived. She bore the brunt of his jealous rages, his resentment of her love for me, and his delusions about imagined affairs with any man within a mile of her. She was working tirelessly to keep the family afloat.

Whilst my father hung around the bars or lay drunk under a tree in the parks of Glasgow’s Southside, my mother, through her work as a typist, kept food on the table.

She had little capacity to support us emotionally. She was too busy holding the roof down in the middle of a storm. She had no time for anything else, let alone infidelity. His possessiveness and violent alcoholism wore her down. She had to find a way to cope.

Despite hospitalisations and repeated beatings, she stayed. And the only way she could endure it was to drink. She drank to numb the pain, to survive what her marriage had become. Her drinking grew worse, adding to the chaos of a household soaked in alcohol and stained with blood.

To escape his attention and vicious intentions, I sought refuge with my older sisters and brother, though they paid the price for hiding me. They were beaten for it. Black eyes, scratches, bruises, all explained away as accidents if anyone had the temerity to ask. Often, I had no hiding place and the inevitable battering occurred.

Growing up with one alcoholic parent, volatile and out of control, and one with a drink problem, just about functioning, meant we had little chance of developing as healthy children.

We four siblings grew up in fear, always alert, ready to run or fight. But I convinced myself it was just a different kind of normal. I thought it gave me an edge, made me resilient. I never stopped to ask why I preferred staying at friends’ homes, or why I was labelled, “bad news,” the boy teachers warned others to avoid. “He is trouble. Keep your son away from that one.”

Superpower

In my immature mind, I believed our home environment gave us a kind of superpower, an ability to survive chaos that others could not comprehend. Our dark humour and closeness helped us endure all of it. We were bombproof, rock solid, and funny and wild. Nothing could stop us. I did not understand it then but have since come to realise the depth of the damage the dysfunction created.

When I was eighteen, my father died in a fire at the family home, caused by a dropped cigarette. To some, it was a tragedy. In truth, it was a relief. The source of the chaos was gone. I know it may sound harsh, but I was glad. Glad that the madness had finally ended. Glad that my nemesis was dead. Glad that the fates of justice had finally delivered their vengeance.

My father’s life provided instruction on how not to live and a stark message about the dangers of alcohol. It has proved to be the single most important lesson I have had. I knew there was a better way to live. A much better way. However, it was much easier said than done.

A rage that burned like a fire

As a child of an alcoholic, I had been written off at a young age by people who didn’t have the slightest idea of what was happening at home or didn’t care enough to ask. It created a rage that burned like a fire in the pit of my stomach.

It possessed me and motivated me to show that I was no failure. In those early days after leaving school, I was driven by a desire to demonstrate to the world that I was worth more than the label ‘delinquent’.

I wanted to rub the faces of those who had consigned me to the scrapheap in the dirt. My ambition to succeed in my career was palpable. I started at the bottom as a Youth Training Scheme retail assistant in a local clothes store, and within fifteen years, I was running the retail operation for half of the UK in a blue-chip company.

Shaking off the shackles

With a wife and two young daughters, I needed to do my best to ensure that they had a very different life to my early experiences. I desired the trappings of success to show the world that I had shaken off the shackles. The big house and the big car followed the big job. To all intents and purposes, I had made it. I had arrived.

But the higher I rose, the greater the demands and expectations I placed on myself. The chronic stress became corrosive. The exhaustion of hyper-vigilance and people-pleasing. The anxiety at the sense of never being enough. The overwhelming fear of rejection. The depression at not performing optimally in every situation to a ridiculously high expectation. It all took its toll, and the only thing I knew that worked to give me relief from the ever-present anxiety was to turn to alcohol.

The only medicine that worked

It was the only medicine that worked. But the other side of the binge brought greater anxiety, depression, and a deadening sense of worthlessness. Life under those conditions was simply unsustainable and, in my mind, ultimately unliveable.

The heady mix was a cocktail of chaos, and looking back, it was no surprise that I fell over. I had what was classed in those days as a nervous breakdown.

The wheels had come off.

Never the same again

Antidepressants and therapy came next. Though I stabilised and returned to work, I was never the same again. The drive had gone. No matter what I tried, nothing seemed to make any difference to the deep depression and high anxiety I felt. I just wanted to be dead, out of the pain in my head and the suffering I was causing for others.

To fix myself, I walked through the doors of an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting in Newcastle City Centre and, for the first time, I admitted that my life was unmanageable. I was to become rigorously honest with myself. I was a mess.

All that was left was the husk of a person, and I needed to somehow build the real me without having much of a clue what that was.

Who I wanted to be

With the support of a great sponsor and the Twelve Step programme in AA, I started to form the picture of who I wanted to be. As I reflect, it was an invaluable time in teaching me how to live, and it gave me many older male role models that I could aspire to. However, it was not a straight path.

After many years of recovery and relapse, I realised that contrary to the mantra, I was not powerless over alcohol. I had power: the power to stop, but just not enough to stay stopped. I knew that my craving for alcohol was both a desire for relief from pain, but also the excitement and the ecstasy of feeling that a dopamine surge delivered.

It had always been the most effective distraction from the problem of living with me. However, in the end, the cost was far too high a price to pay. On binges, I was dangerously erratic and unstable, and the aftermath, the hangovers, the shame, the mental torment, was impossible to live with.

Breaking the cycle

I had to find a way to stop for good. I had to find a way that would allow me to break the cycle of premature alcohol related death and, most importantly, see my family grow. My first grandchild was about to be born, and I found another reason that sustained me. I did not want her or any future grandchildren to ever see me drunk.

My quest for a solution led me to find a scientific treatment that would break the cycle of expectation, that when I took a drink, the buzz would trump the rational knowledge and experience of the chaos that would ensue.

I found the Sinclair Method, an intervention that eliminates craving by blocking the pleasurable effects of alcohol. Taking a pill when I drank disrupted the brain’s reward system. Within three months, I had achieved pharmacological extinction. I stopped taking the pill and have never drunk since. I intend this to be for life.

However, the John Lennon quote that life is what happens when you’re busy making plans could not provide a greater warning against complacency. My wife of nearly forty years has recently survived cancer that was as unexpected as it was unwelcome, so I understand the folly of taking anything for granted.

Living in the present

Today, I try to live in the present and count my many blessings. I can never again allow myself to think that it would be okay for me to have a drink and believe it will be different next time.

When sober, though a lot of the extreme drama had gone, I still needed answers as to why I felt so depressed. I had tried therapy previously and found it made me feel worse. It always felt like a sticking plaster over a gaping wound.

I was being prescribed CBT and psychology books when I needed someone who understood what I had been through and some ideas and perspectives on routes out of the suffering. I was advised by an eminent and expensive psychologist, that when I said that I thought that she might have covered some childhood stuff, she said she was suspicious of clients with a too well-rehearsed personal history.

I’m sure it was said with the best of intentions, but the words percolated, and the thought persisted, it wasn’t my childhood that was the problem, it was me!

Finding peace of mind

Yet, I instinctively knew that my issues revolved around being a child of alcoholics. Until I found a way to understand what had happened to me in childhood, I knew that I would be limited in my progress to find any kind of peace of mind.

I reluctantly sought out another therapist. This time, I was fortunate that I found a counsellor who somewhat understood why I felt the way I did. In the first session, she did an exercise with different sized stones in which I had to lay them out and apply family members’ identities to them.

Despite being long dead, the biggest stone was my father’s. A metaphorical millstone. His presence in my life was akin to carrying his corpse around with me. It enveloped and suffocated me. I had to somehow shed him like a snake sheds its skin. Counter intuitively, the only way I could do this was to somehow find compassion for him.

Understanding why my father was the way he was

It was my first experience of working with my inner child. Meeting his young self in a thought experiment allowed me for the first time to see his wounds and have some understanding of why he was the way he was.

It gave me the perspective and insight to stop blaming him for everything that was wrong with me. I had done that all my life, and it had not worked.

I was impressed with my counsellor’s wisdom and knowledge to use the right tools with me. At the end of my final session, perhaps unsurprisingly, the counsellor revealed that she too was the child of an alcoholic.

I had realised by now that the only solution was to take one hundred percent responsibility for the person I most wanted to be, the real me, the authentically and perfectly imperfect me. I kept striving.

The reasons for my pain

A groundbreaking find was the work of Donna Jackson Nakazawa and her wonderfully informative book Childhood Disrupted. I started to find the explanations, the science, the root causes behind the reasons for my pain and unhappiness.

My Adverse Childhood Experiences, ACEs, held the key. Adverse Childhood Experiences, the potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood, from birth to seventeen years. Of the list of eleven criteria, including various forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, I could definitively count seven, and most likely more.

I identified with the adverse impact of ACEs, my abnormal stress response and difficulties with emotional regulation. My autoimmune arthritis condition. Mental health problems: depression, anxiety, complex P.T.S.D. The alcohol abuse, and the strain on my relationships and overall quality of life.

Adverse Childhood Experiences are not destiny

Thankfully, there was another part of the picture. The positive side is that ACEs are not destiny. While the impact can be significant, they can be mitigated through resilience factors such as supportive relationships, access to resources, and interventions.

I was incredibly lucky. I had many resilience factors, most notably the unwavering support of my wife and my daughters, who stuck with me through the darkest times. My mother and my siblings, during childhood, and later in adult life, were another invaluable resource. A foundation stone of resilience for me is my sobriety.

With solid sobriety, I can now view alcohol as an allergy for me, and like all other allergies, in order not to suffer from the consequences of exposure, I simply cannot ever take it again. I have developed strategies that work for me and help me to live healthily.

A new dopamine addiction

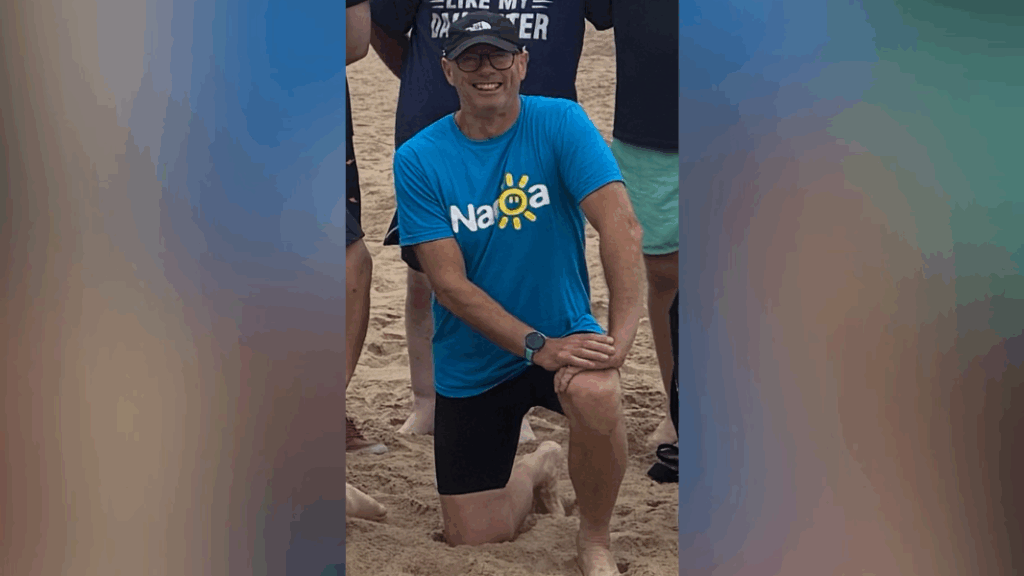

I am quite content to say I have a new dopamine addiction. I swim every day in the sea and the colder the better. This month I’m coming up to 1200 consecutive dips so I can safely say it’s not a passing fad.

It was my love of open water swimming that introduced me to Nacoa. I had started a branch of a men’s support group in Tynemouth, Iceguys Tyneside, and one Sunday, Josh Connolly attended with one of our regulars from another fabulous organisation, Epic Recovery, wearing the bright blue Nacoa hoodie with the message “Helping Children Affected by their Parent’s Drinking” on the back.

After a good conversation with him in the chilly North Sea, I knew that it was a charity I wanted to support and to spread the message that there was help, real help, for children and adults who had experienced similar things to me. I only wished that it had been around fifty odd years ago too.

The diverse expereriences of COAs

Reading the personal accounts on the pages of the Nacoa website, it has never been more apparent to me that the journey of the child of an alcoholic is incredibly diverse. However, the characteristics we share are evidence enough that despite the variation in circumstances in which we were raised, the outcomes are incredibly similar.

The sense of not being enough. The constant people pleasing to assuage the fear of rejection. The lack of trust in authority figures. The latent rage that emerges when least expected. The depressions, the anxiety, the self-doubt and crushing lack of confidence. The avoidance behaviour and the search for solutions. The self-medication, the distractions, the fads, the obsessions.

Anything to fill that chasmic hole, the sense of emptiness, and the ennui. The need for excitement, the craving for chaos, the absolute dichotomous thinking, and the search for some respite from hypersensitivity and the hyperactive mind.

Taking better care of myself

The search for solutions has also led me to take care of myself better physically and mentally. I train most days and have restarted playing organised football. I have also taken up running and am looking forward to running in a number of races this year. On the creative side of things, I have developed a love for writing.

During Covid, I started writing and haven’t stopped. I have written two creative non-fiction novels based on my own experiences, Mammy’s Boy and The Art of Redemptive Suffering, and numerous short stories including The Orange Cord. Unsurprisingly, they explore themes of alcoholism, violence, and poverty. (I plan to self-publish them this year).

I recently gained my Master of Arts in Creative Writing at Newcastle University. I achieved a grading of Distinction. My peer group consisted mainly of privately educated graduates and the professional and middle classes.

My lecturers were professors who had taught at Oxbridge, multiple times published authors and playwrights whose critically acclaimed work is performed on television and radio. They all told me I could write. But my sense of being not as good as and not enough convinced me that I shouldn’t believe them.

I thought they were just saying it to make me feel good about myself! Ultimately, my commitment to be the best version of myself won out and I stuck it out until the end.

For a short period after I graduated, I told everyone I knew that I got a distinction in my master’s from Newcastle University. I cringe when I think that people might have thought I was boasting about my award. I genuinely wasn’t, I was simply conveying my astonishment that the poorest boy in his Glasgow primary school, ridiculed for his shabby clothes and poverty had achieved an academic accomplishment of such magnitude at the age of almost sixty.

Gratitude for my life

I now have an amazing life. I have a wonderful wife, two amazing daughters, four incredible grandchildren, a warm and safe home that my big labrador owns, a successful small business working alongside my two daughters and a great little team of good people, a great relationship with my siblings and extended family, loyal friends, and a list of experiences and achievements that I am now just about able to look back on with fondness and pride.

None of these are boasts, just recognition of how lucky I am, and how grateful I am for everything I have in my life.

Breaking the cycle of alcoholism in my family has given me a chance to make up for lost time and lost opportunities, and to be the person I most want to be. I hope my story helps those who have experienced the darkest of times that there is always the chance of a better future.

Who knows what the next chapter will bring, but I hope it includes some more open swimming, writing, running, and spreading the word about Nacoa.

Preventing ACEs is crucial for promoting healthy child development and reducing the long-term burden of disease and suffering. If I can help spread the message of this wonderful organisation, even in a small way, it will be worthwhile.