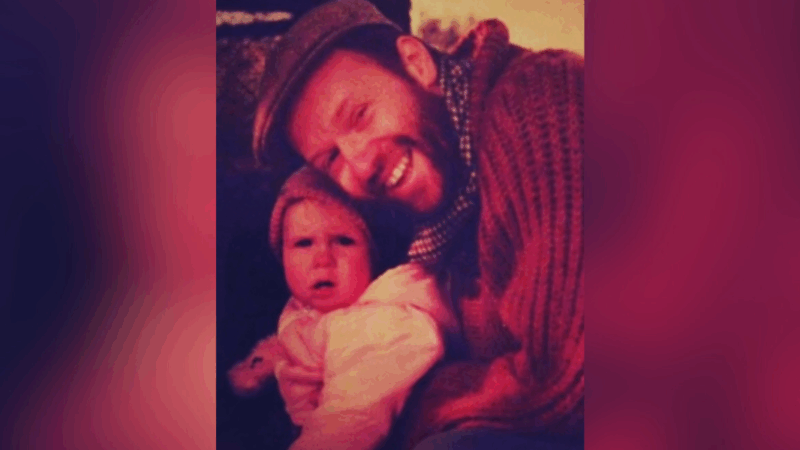

Me and my dad

My first thought as a title for this was ‘Me and my Alcoholic Dad’, but to completely characterise him as an alcoholic would be a disservice to him and to those who knew him. He was an extraordinary man in so many ways, and he was an equally extraordinary father.

Thus, he was loved and adored by many. Despite this though, he was still an alcoholic.

My Dad played a monumental part in my being brought up (as any stay-at-home father would). When I was a child, he was the most wonderful father. He encouraged me in every conceivable way during my time at school.

He cheered me up with his extraordinary sense of humour when I was sad. He educated me with a mind that would have made him a good academic had he gone to university. He was, in many ways, the perfect Dad who was able to instil in me a goodness that continues to make me flourish in my own way today.

Finding out as a child

Fortunately, Dad was sober for much of my childhood, and when he wasn’t sober. My Mum did her best to protect me and my brother as much as she could.

However, at about the age of nine or ten (or thereabouts), I noticed that Dad started acting strangely sometimes. I once remember walking in on Dad doing something with a bottle of alcohol, and he quickly hid it and tried to convince me that I saw nothing.

I grabbed a piece of paper, wrote ‘please stop’ on it

I also recollect finding a bottle in a storage cupboard and instantly realising that Dad might have a problem with alcohol. In response to finding the bottle, I grabbed a piece of paper, wrote ‘please stop’ on it and attached it to the bottle with a blob of Blu-Tack.

I knew that there were bad outcomes for those addicted to alcohol, and it made me worry in ways that a child shouldn’t have to. It was around this time, I suspect, that I started to develop what would later be identified as an anxiety disorder.

Dad never acknowledged the note

I can’t remember much more happening for a while after I found the bottle. Dad never mentioned or acknowledged the note I left, and the bottle not long after had disappeared.

This was until 2013 when Dad chose to attend a church fête drunk with me and my brother. I noticed he was a bit sluggish and unsteady on his feet, but, as a fourteen-year-old at the time, I struggled to identify the signs of Dad being drunk beyond that.

It wasn’t until my Mum arrived later that day that she noticed his drunkenness. She was angry with him, and she instantly took us back home in the car. What followed was a period of horror and completely unrelenting despair.

Mum, upon realising that she couldn’t protect me from it any longer, revealed to me that Dad was an alcoholic. Mum set Dad an ultimatum, sort himself out and get off the bottle before long or he’s out of the house and moving elsewhere.

I had always thought that I had lived in a home that was happy and stable – a false reality of mine that had been smashed within a short few moments.

Throughout that year, Dad’s alcoholism became worse. He’d get drunk while Mum was working which would invariably result in arguments between the two later in the day. It was an extraordinarily dreadful experience.

I’d attempt to block out the shouting

I’d try to switch off from what was happening at home. I’d attempt to block out the shouting by watching television or seeing something on my computer. It was the only point in my life where I enjoyed school simply for the fact that it wasn’t home.

This continued for a good while until Dad suddenly became hospitalised with sepsis. After a long stay, he returned home and didn’t touch a drop of alcohol for roughly four years.

They were wonderful years when I had Dad, whom I loved, back. We did wonderful things like go on days out and go on holiday. He supported me through my GCSEs and helped to get me going when I struggled with starting my A-Levels.

It was a wonderful and joyous time when I could feel happy to be at home again. A time which I didn’t want to see end. It was a tragedy, then, that it did end, and he fell back into alcoholism again.

Relapse

In 2017, Dad started acting strangely once more. We tried to make excuses to ourselves that it was just because he was tired and exhausted on some days, but it wasn’t the case.

He was intoxicating himself and doing so at a scale that he never managed previously. It was a traumatic time and a period in my life that I still have nightmares about to this day. His alcoholism turned him into a different person – a wholly unlikable and manipulative person.

He would say horrible things to my Mum and lie to me brazenly. The man he became was not my Dad, and was instead a completely obnoxious person who were forced to contend with on a daily basis.

An unsteadiness

In addition to his increasingly foul demeanour, he was unable to care for himself at all. On one occasion, when Mum was out, I was walking across the landing at home when Dad, who was extremely drunk, suddenly appeared standing halfway up the stairs.

He was trying to say something to me through his slurred speech before an unsteadiness on his feet became apparent. He grew increasingly unstable and I knew, because he’d do so regularly when he was drunk, that he was about to collapse and fall. Keeping in mind that he was halfway up the stairs, I became acutely aware that he could badly injure or even kill himself if he fell in the wrong way.

Given that there was no way to prevent Dad from falling, I had to get to him and, effectively, pull him towards me so that he’d fall up the stairs rather than down them.

This worked and he was fortunate this time, but if he were in the house alone, he could fall prey to a much more serious accident. This, for me, reinforced a growing view that we wouldn’t be able to look after him if he didn’t commit to sobriety soon.

The end

A considerable amount of time passed, and things only got worse. Around Easter of 2018, Dad ended up in hospital for the second or third time in a few days after going AWOL, getting drunk, and being picked up off the street. Eventually, me and Mum made the decision that he, finally, couldn’t stay with us.

We couldn’t deal with him anymore and, long story short, he no longer lived with us. It wasn’t as if we didn’t care for him. We hoped that he would be able to find the help he needed. It was just a fact that, if we didn’t move on with our lives without him in our home, we would have suffered enormously. He had money that we hoped he would spend on staying at a hotel until he could get some proper accommodation. But, unsurprisingly, he spent the money on alcohol.

After attempts by the wider family to help him, he stubbornly resorted to alcohol and, before long, he became homeless. Soon after, he was assaulted in the streets and beaten badly. To the extent that he could never live a normal life again, with or without alcohol.

I never saw him again after that. I did consider doing so on a few occasions, but I didn’t think it would be good for him or me. For five more years, he spent his days in a nursing home with a deteriorating quality of life until his death earlier this year.

How I responded to it all

Throughout my life, I never spoke about what was happening at home to those beyond my household or my extended family. Only a few people knew.

Throughout my childhood at school or my young adulthood at sixth form and university, I went to great lengths to prevent any of my friends, even my closest, from knowing. Even today, I expend some effort to soften the perception that others have of my experience.

One of my flaws is that I’m a very anxious person, and I have an anxiety disorder that can have an impact on me. There’s something about expressing my vulnerability that unsettles me, and I get anxious that people would see me differently or less of a person if I were to be truly honest about what happened.

Sometimes, I worry that others might blame me for what happened. Indeed, I’ve spent years of my life wondering if I were culpable for Dad’s own mental health troubles, and whether my being a better son could have prevented his alcoholism.

I worry that others might blame me

I have gone to great lengths to even consider whether I was to blame for his eventual quality of life and death. It’s easy for me or others to say that I’m not, but it’s not something so simple to intrinsically accept (though it’s getting easier).

To put it simply, I know I’m not to blame, but I don’t feel content with the answer yet, and that’s okay. It’ll take time. One day, I will accept it completely, and I look forward to it.

Beyond that, though, if there is a single thing Dad’s alcoholism has taught me, it’s that you shouldn’t be discouraged from getting help. Dad had an aversion to getting help for the mental health struggles that fuelled his alcoholism.

We all tried to encourage Dad to get the help he needed, to no avail. I can theorise as to why, but the most important thing is that you shouldn’t feel that way. Getting help is a good thing and something I have done to deal with my own mental health struggles.

Anxiety

Once upon a time, my anxiety made me insular, extremely quiet, and terribly meek with a stubbornly pessimistic outlook on life. Getting help from counsellors and therapists has been an extraordinary help for me, and I support anyone who needs help to go about seeking it. So much so that I feel the confidence now to be able to share my experience of being a child of an alcoholic here.

I feel the confidence now to be able to share my experience of being a child of an alcoholic

I think it would be amiss not to mention that, at the time of writing, I’m okay. I’m doing fine. I’m getting on with my life and doing my best to remember the good man Dad was.

So many of his good qualities as a father and as my best friend have made me a better person. His encouragement of me in my academics has lasted for me as I go into my second year of a PhD. Despite all the trauma and the problems, I’m happy and progressing.

My mental health is even improving and I’m becoming a more confident and able person. Sure, I’ve needed help, but that’s no bad thing. And to be able to admit that I’ve needed help has made life far less painful than it otherwise might have been. I am extremely fortunate because things got better for me.

My final words

I wished I had known about Nacoa when Dad was around. Knowing that there were others around for me who knew what I was experiencing would have been a monumental help. Therefore, for anyone who is reading this and is going through similar circumstances, I hope you’ve been able to find some comfort in knowing you’re not alone.

To end, I think it would be appropriate to repeat the message I shared the day after my being informed of Dad’s death:

‘Yesterday, I was made aware that my Dad had passed away. He was, in so many ways, an incredible man. A brilliant man. An irreplaceable man. And for the vast majority of the time that I knew him, he was the best father a child could be fortunate enough to possess.

‘As I think of him, my memories quickly return to my childhood. The laughter we had as he walked me to school. The fun we’d share when we spent the afternoons painting together. The wonder I’d feel as he shared that intelligent and wonderous mind that he had with me. Without him, I would not be the person I am today – I would instead be something much lesser.

‘It’s been roughly five years since I last saw Dad, and our departure from each other’s lives was not an amicable one. Nonetheless, I shall choose to remember and mourn the undoubtedly extraordinary man he was. In that spirit, I thank those who cared for him in his final days and years, and for those who were with him when he died.

‘Farewell, Dad. I will forever be grateful for the years of love you gave to me. I shall remember you. Forever.’

Josh

For more experience stories, go to Support & Advice.

Piece published for Addiction Awareness Week – Taking Action on Addiction.